The Divine Game of Pinzatski

Back in 2015 my wife and I visited the small village of Glen Coe in western Scotland. We chose it chiefly because of its proximity to the West Highland Way, a popular walking trail that runs 96 miles across the Scottish Highlands.

Formed into a U-shape by an ice-age glacier, the trail narrows sharply at a point called the “Pass of Glen Coe.” This pass is famous not just because it served as a location for “Monty Python” and “Harry Potter” movies, but also because of its stunning geography.

Lying between the six-mile-long notched ridge of Aonach Eagach and the truncated spurs of Bidean nam Bian, the glen is an ice-worn valley mantled with screes and debris from the mountains. The region includes waterfalls, vertical outcrops, and hanging valleys.

During our three-mile hike up Stob Mhic Mhartuin, Phaedra and I played a game that we have often played during our walks in nature. It’s a game I learned about in seminary called the “Divine Game of Pinzatski.”

Conceived by Arthur and Ellen Pinzatski, the game calls for one person to point out an object in nature that the other person must then state what the object might say about God and why.

I’d point to, say, a bit of green moss, and Phaedra would say, “The gentleness of God,” and explain why she thought so. Or she’d point to a boulder-strewn cut in the mountain, and I’d say, “God’s severe mercy,” and explain why I thought so.

Playing this game over the years has taught us to pay attention to the details in creation and see that there’s no such thing as generic moss but rather things like Perthshire Beard–moss and Woolly Hair–moss; that rocks are not just rocks but can be volcanic or sedimentary.

It has taught us to hear the voice of the Maker in the things that he has made—that moss and rocks do in fact praise God in their own unique language. It has taught us to re-see ourselves as humans, how small we are yet how well-loved we are, too, in this theater of God’s glory.

And it has taught us to see what the psalmist saw long ago, in Calvin Seerveld’s translation of Psalm 19:1–4:

The heavens are telling the glory of God.

The very shape of starry space makes news of God’s handiwork.

One day is brimming over with talk for the next day,

and each night passes on intimate knowledge to the next night

—there is no speaking, no words at all,

you can’t hear their voice, but—

their glossolalia travels throughout the whole earth!

their uttered noises carry to the end of inhabited land!

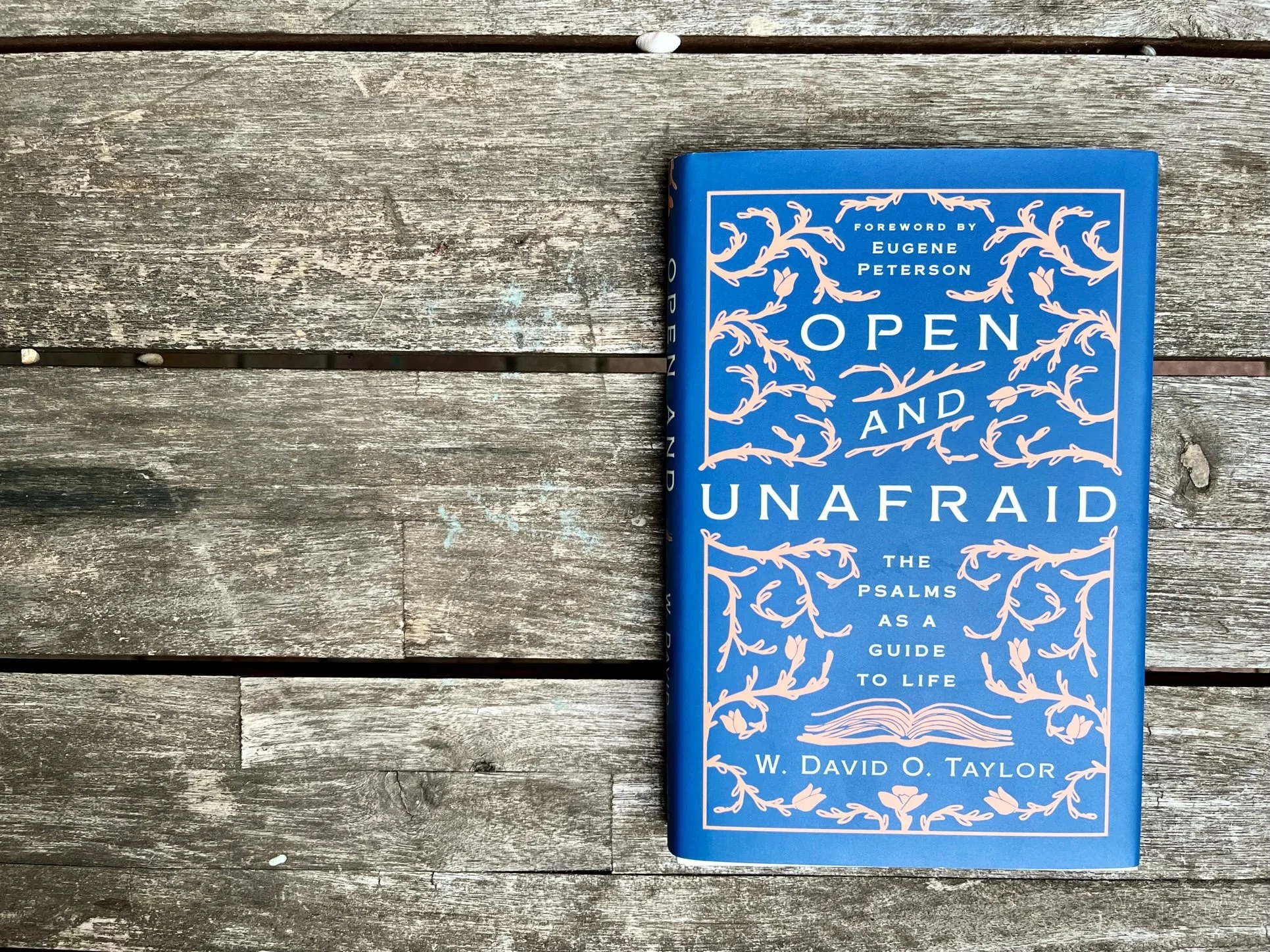

I write about all of this in my psalms book, Open and Unafraid: The Psalms as a Guide to Life, but I’ve also assigned the “Divine Game of Pinzatski” in my theology classes at Fuller Seminary, and I love to read my students’ reflections on their experience of the game.

Let the games begin!