The Agony of Prolonged Waiting

Waiting is one thing. Waiting, that is, for the first snow of winter or the much-anticipated birth of a child can be a lovely, even if demanding, thing.

Prolonged waiting, however, without any hope of relief or answered prayer is another thing. Waiting, for instance, for a spouse to show up (who never does) or for a spouse to shape up (who never will) can be pretty miserable business.

(The same holds true for those who wait interminably for the repair of a marriage, the cession of a war, the rectification of an unjust judgement, the healing of a disease, the return of a prodigal, or a way out of the vicious cycle of poverty.)

The house that we’re building isn't anywhere near-complete, but we need to get out of our rental in a week’s time and relocate to an interim place, and thank God for an angel friend who’s found us a place to live in the meantime.

But still. It's back to waiting, ever and always the waiting; and the stress, so much stress.

I’ve been working towards this home for nineteen years now. It’s been a three-year construction project but it’s been nineteen years of scrupulous saving and careful decision-making and unforeseen delays and anticipation of a permanent home. And for a missionary kid like myself, who continually struggles with a deep sense of rootlessness on this planet, it’s hard on the heart.

“It is winter in Narnia,” Mr. Tumnus tells Lucy, “and has been for ever so long…always winter, but never Christmas.

However admirable, even virtuous, then, authors are able to make the experience of prolonged waiting sound in a book, the real-time experience of such waiting can feel crushingly oppressive.

It tempts you always to doubt the goodness of God and it threatens to turn you into the worst version of yourself—crabby, anxious, stingy, and prone to do decidedly foolish things to force the hand of Providence in the direction of anything that will relieve the painful feeling that you've been unjustly abandoned to your own devices and that the best you can hope for is small doses of self-medicated happiness in the face of an overwhelming feeling of powerlessness.

You practice, to the best of your ability, an attitude of gratitude and you keep saying out loud all the things that are good about your life, as it presently stands, but you can't escape the feeling that you're simply recycling platitudinous motivational poster material:

"Difficult Roads Lead to Beautiful Destinations" (except when they don't).

"The Best View Comes After the Hardest Climb" (save for those times that you climbed to the wrong side of the mountain).

"The Pain You Feel Today Will Become the Strength You Feel Tomorrow" (unless, of course, you wake up in a war-torn world and utterly despoiled of life).

"All Things Are Difficult Before They Are Easy" (excepting taxes, trigonometry, and throwing a no-hitter).

These things are true, but only in a strictly qualified sense, and they never tell the tale of the grey zones, where the ambiguities and complexities of life predominate for most people; for people, that is, who choose to remain alert to the jagged textures of faith in God and honest about the often-confused, always-mysterious condition of the human heart.

You know at some level that your feelings of utter woe might be irrational, for, with eyes to see, you'd spy plenty of signs of goodness all around you. And there's always somebody worse off than you, in a way that you can’t fully quantify, but that judges you and finds your self-pity morally wanting. And maybe it's just a first world problem. Or maybe you’re just being a whiner.

But still.

A feeling's a feeling no matter how small.

And it's ok to feel sad or disappointed in the face of interminable waiting, if we’re willing, that is, to take the psalms seriously rather than to theologically seal them off from the Gospels or to pit them against triumphant one-liners in the Epistles.

One of the things that I’ve found helpful under such circumstances is to surround myself with physical objects of remembrances, things that would obdurately stare the truth back at me in their material permanence—the truth, for instance, that God’s mercies are new every morning, that I am never alone in my sorrows, and that I shall see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living, truths that all-too easily slip through our grasp under the stress and strain of life in an often-unpredictable and frequently unfair world.

In my case personally, these things could be an icon, a photograph, a lemon tree, or an old pair of shoes.

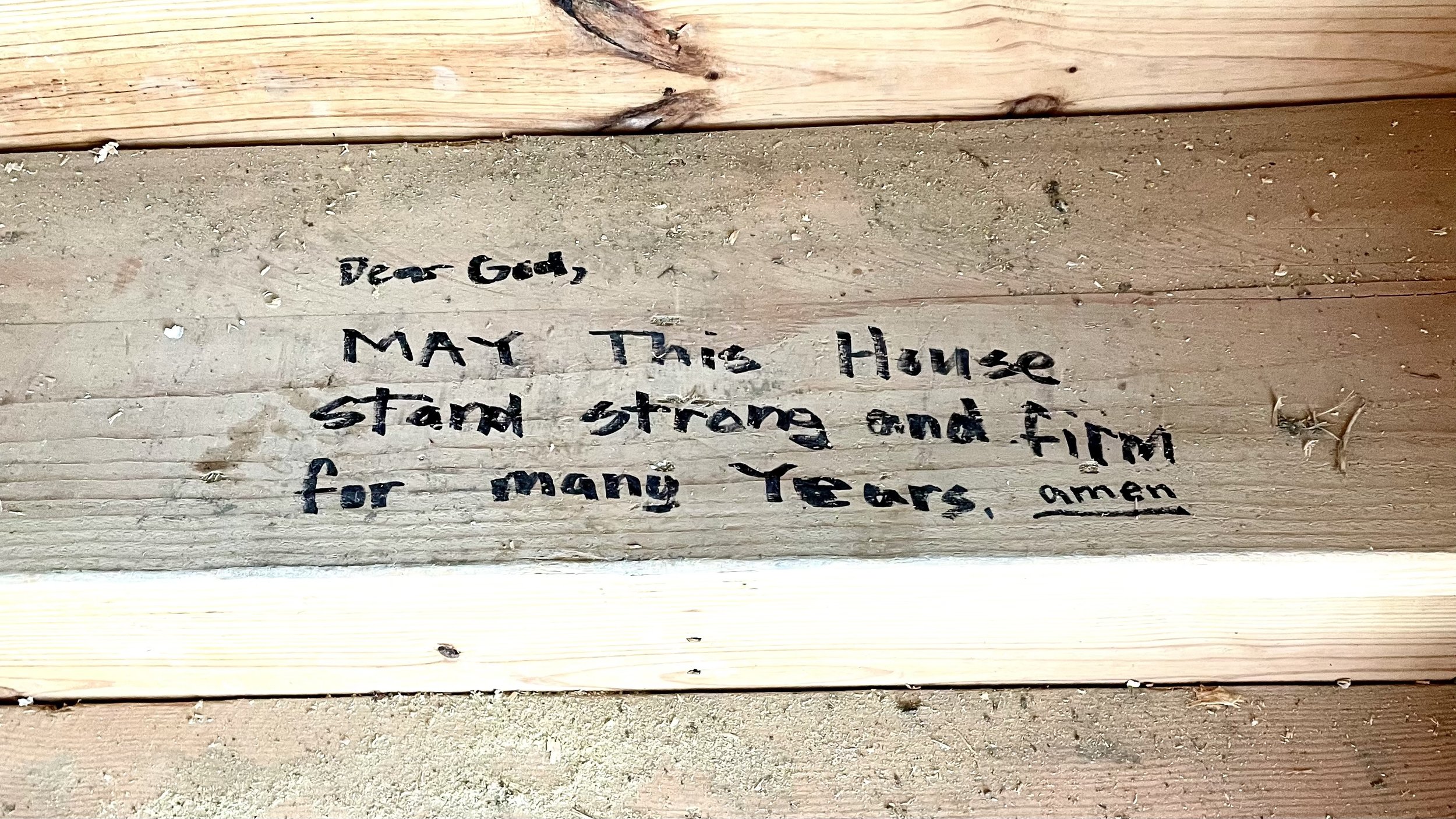

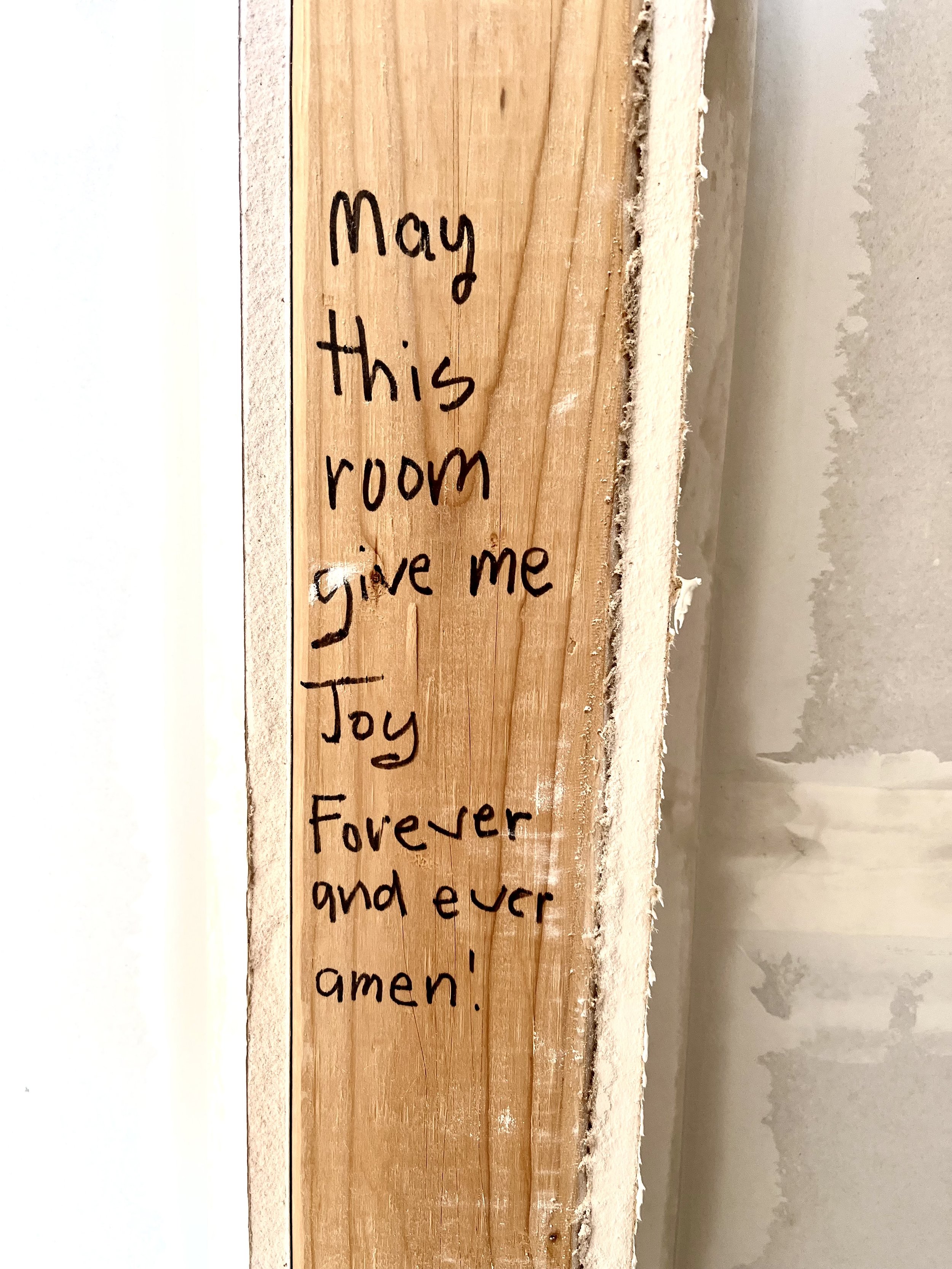

In our family’s case, we’ve written a series of prayers and blessings throughout the skeletal frame of our house in order both to anticipate our eventual homecoming and to abide with us in the years to come. They’ve been scrawled onto plywood sheets and two-by-fours and stair steps in order to bear witness to our hope for this home.

“But, wait,” you ask perceptively, “isn’t all of this text invisible by now in the construction process? Aren’t these prayers and blessings hidden behind layers of drywall and paint?” Yes, they are, and there’s a chance that they’ll even disappear with time.

And this is where our ritual turns into a metaphor.

While the prayers and blessings won’t be able to bear visible testimony to God’s faithfulness to us, they will nonetheless remind us of the truth, even if only at their molecular level, that while certain things in life may remain unseen to physical eyes, this does not make them less real, less powerful.

They’re there. They’re there as much as angels are there, always and everywhere.

They’re real. They’re as real as the invisible, immortal God only wise is real.

They’re true. They’re as true as the Holy Spirit’s ceaseless intercessions on our behalf are true, praying that we might remain sure-footed and truehearted.

They’re certain. They’re as certain as the sorely needed prayers of the saints are certain.

They’re solid. They’re as solid as the One who gets us from the inside, the One who does not solve or even remove our pain but who shares it with us, stays near us, for us. They’re as solid as the incarnate Christ is solid, still to this day, standing at the right hand of the Father.

One also needs, of course, good friends, flesh-and-blood friends, who won’t quit on you, who won’t tire easily of your incessant lament, and who occasionally will take you out to the public park or to the movies in order to help you to escape the inexorable spiral downward into a wretched self-absorption.

The Celts had their cairns. The Jews had their Ebenezers. We will eventually have our own stones of help and remembrance and thankfulness on the property.

For now, we’ve got invisible but ever-present prayers, reminding us that our waiting is not in vain and that our seemingly endless waiting is not an exception to the Christian faith but rather at the heart of it, if Israel’s four-hundred-year sojourn in Egypt and Isaiah’s seven-hundred-year wait for the Messiah’s arrival are proof of God’s good, but often inscrutable, ways.

Our prayer, in the end, is that such physical objects of remembrance might sustain us in hope in the agony of prolonged waiting, both now, with this house, and in the years to come, with other matters that will test the heart.

Our prayer, particularly during this season of Advent, is that they might keep us close to the heart of the One who waits us with us and who would remind us that we are not insane or, worse, faithless for struggling with doubt, but instead that it is through the struggle, or agonia, to trust God in this difficult experience of waiting that we discover by grace a deep and abiding peace that surpasses any rational capacity to fully comprehend, a peace that only the Spirit of God is able to secure in our oft-feeble and fickle hearts.