“To Hell With Your Money!”

I can still remember the first time that I used the f-word. It was December 6, 1985. I was thirteen, rather diminutive for my age, and naïve like most missionary kids who’d never lived in the States. My family had recently moved to Deerfield, Illinois, and I was skiing for the first time in my life.

Heavy winds gusted across the Wisconsin hills of Wilmont Mountain; giant halogen lamps glowered above the Black Run that I had dared myself to ski; and pretty girls with long blond hair swished around me, fluttering with laughter. Seconds into the run, I tripped over a mogul and tumbled head-over-heels, losing my whole wardrobe in the process—toque, gloves, skis, hat, a boot.

While tumbling down, I cussed, loudly. Skidding to the bottom of the hill, I surprised myself by my own temerity. In the moment, it had felt like the most natural thing to say. Extreme pain plus extreme embarrassment seemed to necessitate the f-word. It named the experience rightly.

Linguists tell us that the f-word is one of the more satisfying words to say out loud, and I can certainly attest to that fact. It explodes in the back of the mouth like a baseball cracking a ball flying in at 95 MPH. Its grammatical uses are also near-infinite, being used as a noun, an adjective, an adverb, an intransitive verb, a conjunction, and as infix of disbelief, and in my case it was a cry of dereliction. Afterwards, however, I felt mortified and somehow responsible for the abomination that causes desolation.

But to what species of language does it belong and what purpose does profane language serve in human societies?

As anthropologists explain things, there are three basic categories for profane terms: sex, bodily functions, and the gods. In most societies, these categories are protected by a register of taboos which preserve the good order of things both natural and supernatural.

But the socially permissible barometer for what counts as offensive language often shifts with time and setting. For instance, the 14th c. poet Geoffrey Chaucer made liberal use of “ers” and “fart” in his epic poems, while the 1611 KJV used what might be regarded today, by some, as suspect terms—dung, piss, whore.

In nineteenth-century America the word “leg” was considered indecent; the proper term was “limb.” And in the late Middle Ages, a “hussy” was a housewife, while in the world of vets, a “bitch” is always a female dog. In Eugene Peterson’s translation of Acts 8:20-23, he has Peter swearing to high heaven:

“To hell with your money! And you along with it. Why, that’s unthinkable—trying to buy God’s gift! You’ll never be part of what God is doing by striking bargains and offering bribes. Change your ways—and now! Ask the Master to forgive you for trying to use God to make money. I can see this is an old habit with you; you reek with money-lust.”

(I also have a vivid memory of “Emergent” Christians of the early 21st century, largely of Baptist origin, relishing the saying of swear words, as if it were a badge of verifiable coolness. Each sought to out-Tony-Campolo the other, it seemed. This stood in sharp contrast to my more conservative brethren who repeatedly quoted to me a single term from Philippians 4:8 [hagna], without any attention to the immediate context or to the larger frame of Holy Scripture.)

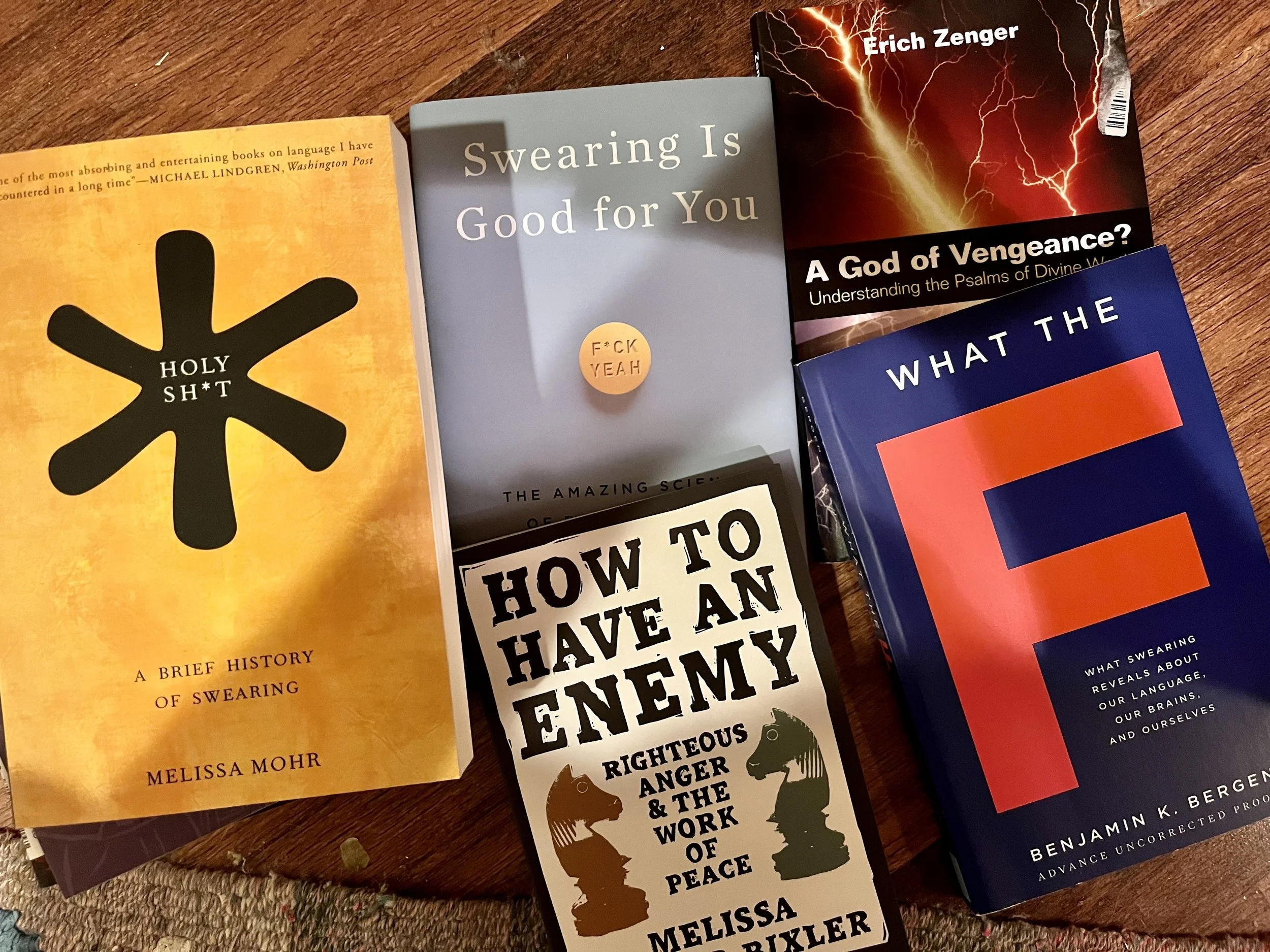

My interests in profane language, it should be said, are chiefly theological, but I’m also fascinated by its sociological functions as well as its overlap with the curse psalms which I write about in my book, Open and Unafraid: The Psalms as a Guide to Life.

Certain things in this world, at some fundamentally ethical level, need to be told to fuzz off, like sex traffickers, abusers of any sort, and dictators. It’s the word that “fits” such profanations of God’s good creation. But it’s also a term that should come with a warning: “handle with care.”

There’s a good reason why societies throughout history have safeguarded the use of “profane” words with care-filled taboos. It’s not just fuddy-duddy business. Words retain power to bless and to curse, to wound and to heal, and it couldn’t hurt every once in a while to preserve their good, holy purposes, while also resisting extreme reactions either way.

For now, though, I’ve got to pack up these books and hope that there’ll be a day that I can turn these thoughts into a proper essay, as I keep in mind Shakespeare’s judicious advice in “Henry IV, part II,” namely, that “‘Tis needful that the most immodest word/Be looked upon and learned.”